~A Long-Form ‘Review’ of the Melanie Bonajo Show at Akinci~

Unlike what is common in most men, the slowing of the blood formation system until dysfunction, my erections didn’t start till I was twenty-eight, and even then I could only get a semi. As a child I wondered what was wrong with me. I saw my boy friends tuck their erections into their waistbands during school and rub themselves on the sides of tables when the bells rang their peel. I would emulate them in an operation allowed by my generous endowing of foreskin and the agent of a particularly strong elastic that held my underpants. It did the job pinning it to me, but alas, after a few pressings of myself against the wood of the table, my soft penis would droop down my right leg and I would be left chastised and lubricious. Neither when I was alone, nor sharing myself with another, could I get the slightest bit hard. I would emulate the perversion of my friends in class, tensing my buttocks, convulsing my crotch, rubbing myself in mimesis, but I knew I would never feel the pleasure that they felt.

With sex, even masturbation, off the table, my world, instead of narrowing, opened up. I could see that I could concentrate more, and was much more akin to abstract concepts. I was predisposed to math. Logic games excited me, and my investigation into composition as a form of self-referentiality that ended in negating, by ultimately annihilating itself, led me to New York in 1961. I was to witness the legacy of, the development, and ultimate break from, Cagean silence.

Henry Flynt (whom I’d met in 1962) developed ‘concept art’, a progenitor to ‘conceptual art’, on the basis of the Cagean understanding that music is sound. The material for Cage was sound, as opposed to the music proper—its notation, its analysis, etc. Flynt wanted his concepts to be the material of concept art, but because concepts were different from sound, not as defined as notation, language had to be used. Although concept art and conceptual art shared the interest in the dematerialisation of the art object, Flynt had no hangups about the artwork’s role as a commodity—for which the art world has been in a losing wrestling match with Duchamp for the last 100 years, unable to move past the artistic tropes of authorship, composition, and intention, birthing such infinitely dull practices as the cold ‘institutional critique’. Both Cage and Flynt were performative, no doubt, but the line that Cage took, which favoured the ateleological undetermined sound as liberatory (American), against sound as oppressive (European), eventually led things back to a high art / low art dichotic stasis. We had to move past Cage, but the best way out of his thought, it seemed, was through it.

Concept art came when Flynt, along with Tony Conrad, started making his own ‘word scores’ via La Monte Young. These pressured or extended the composer’s presuppositions to such a degree as to transform them, and thereby surpass or get beyond them. These word scores held awesome power. We were able to presuppose 4’33”—how were we to remain silent if the performance had already happened, or was yet to happen? Ultimately, we were time travellers. The word scores were pure language, but as expressive as a mathematical equation; they could be run through identically by anyone. Shed your ego, accept the axioms, and you could move through the logical steps. At the time I was identified with these word scores for their mathematical purity, but now in my old age, I realise that what we were doing had a religious impulse.

Still, the break from Cage was yet to come. The impulse to transmute Cagean silence out of music and into art via the word score, birthing concept art, was not enough. It was around the time that we were floating the idea that, if a sound is a sound, then the actions that make up daily life, if done entirely to one’s personal taste, could also exist freely. We aimed to take seriously the shifting of one’s weight from one leg to another. The name for Flynt’s venture into the quotidian was ‘acognitive culture’. It was at this point that I showed Henry my annihilated member (he used his Southern charm), which I posit was the model for his acognitive culture; The form of my erect penis, by societal standards, was objectively good, for my partner and for myself. However, my penis could never achieve this form. In algebraic terms, the variable had no chance to ever be variable, meaning, instead of working out the sum, we changed the sum. What a wretch I have now become, but yet it was my body, my young eunuch body that I once possessed, that was the basis for acognitive culture, an autistic movement against Cagean multiplicity.

One of the offshoots of acognitive culture would eventually lead Henry to pen the ‘creep manifesto’. In the original manifesto—and this is testament to the stamp Henry’s thought made on the world—the term ‘involuntary celibate’ was coined. Once again this term would be swallowed by the mainstream and become homogenised, in an analogue to conceptual art, only to be spat out later by the In(voluntary) cel(ibate) movement. But the Incels don’t go far enough, instead wanting their low art tendencies to be accepted. We, however, touted surgical improvements for the original creep, going so far as to extend our creep tendencies, for which annihilating the erection was one supposed operation.

Just as a person who loses one sense gains a more acute understanding of the others, my body, which was the Kritian touchstone of acognitive culture, had gained a certain cloacal obsession. This was all lost when, at the point of our zenith in the mid-60s, I started to chub. At the time Henry was staging symbolic pickets—he went for Stockhausen—I saw these as needless, and actually reaffirming a European High/ American Low / dichotic. Flynt never understood America as an imperial state. But my hatred for my homeland was real. And as I started to feel full erections in the 70s my concentration became shot. And with my faith in mathematical purity waning, I left for Europe.

The maintenance of what could be seen as a healthy sex life—where my sex met with the opposite sex in the 80s and early 90s—led to a desensitisation of other parts of the body, causing my disavowal of any interest in the avant-garde. Past the 90s I was in such priapic discomfort that, eventually, in ouroboric manner, I retreated. First, mere touch from the opposite sex would give me an erection, then it became the sound of an effete voice, until eventually reading feminine names in letters or any kind of signage with girly suffixes would give me The Swells. Upon arriving in Amsterdam, I took the name Iain Sterdam and managed to take residence in a Michel de Klerk social house. My daily route is thus: I awake at around 07:00. Before breakfast I spend the morning reading the news on my computer. Because of my morning wood, simply reading the word the is enough for me to ejaculate. I continue this operation for two hours until my balls have completely drained. After which, I reach orgasm when buttering my toast, and am able to, through the drying out of my active urethra and the waistband tuck, leave the front door.

On my days off from the gallery reviews, I wander through the city. Unlike the German and French languages, the normative cases dropped out of Dutch in the 1940s, meaning I can move around the city somewhat freely without coming into contact with the grammatical gender of a (feminine) object. Whenever I go out I am always ready to encounter one. Last week I overheard some youths talking about cassettes, which, along with making me reminisce about the 80s, caused The Swells. I don’t take the bike. I keep a relatively good exercise regime up thanks to my vigour—it’s not my old age that limits me—I can’t take the bike anymore, as the last time the rubber saddle met my prostate it started The Swells, and with the flow to my urethra cut off, it all sloshed backward in prolapse and I shat my drawers. So instead I walk with my head down, hawk-eyed, bowing at the cracks in the concrete, weeds, cracks, weeds. I rise from my bow so as to cross the street, or to carefully avoid any piece of litter, say a cigarette with a lipstick stain around its filter tip — ‘cos that’d send me.

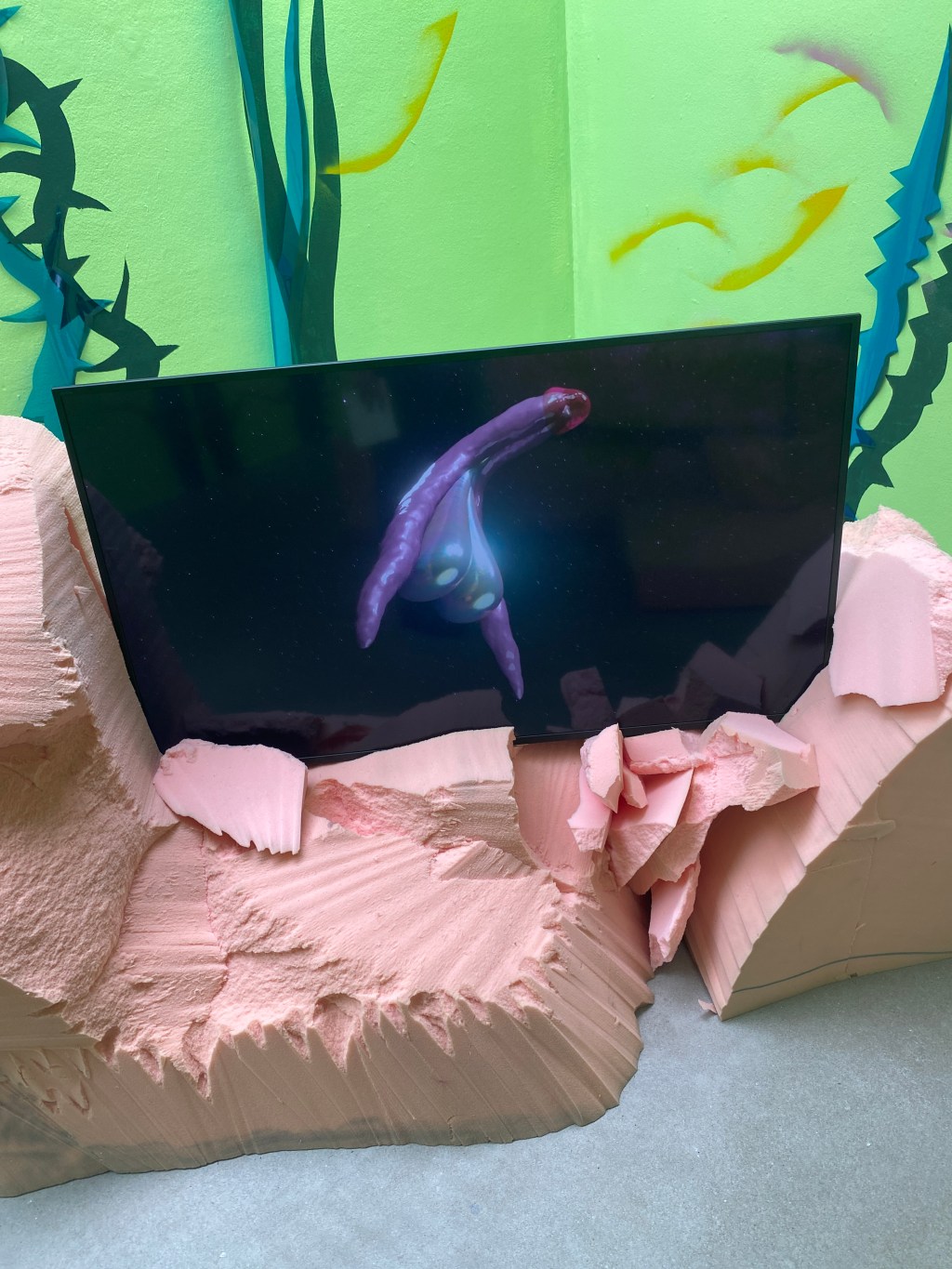

At Akinci they told me they were looking for queer neurodivergent people to participate in an art project. As I had been the original acognitive creep, I thought I fit the bill. When I arrived, to my surprise, the Facilitators were pleased to meet an older person. The Swells were in full effect as, despite them being taller than I, and my Anti-Visual-Aid contortions, I could recognise their effete voices. So as not to embarrass myself I muttered out my condition. The Facilitators looked concertedly at each other, knitting their brows in synchronic unison, but abated me by saying that they would find a way to make me sexually compatible. They took me to a small plump man who they called the Somatic Body Coach. He was a pallid, gaunt creature, with ashy blonde hair and large deep eyes, and a somewhat tragic mouth. I explained to him The Swells, and he handed me a consent form, which I signed. “Iain, you’re good to go!” The Facilitator winked—a wink that highlighted the heady, skill-less nature in which her makeup was applied. Winked, at me! Naturally in my daytime visits to the Art World, I’d come across disinterested female gallery attendees, thus developing bodily exercises, like jittering the leg, for when they’d address me. But to be addressed by one of the Facilitators, and by the one with the blue streak on her face—wowee! I was so jittery that my leg was sent into overdrive, and for the first time since The Roxy, around women, the blood was humming and my jitters had reached a stillness—the beat became a drone.

The space was vast. Had I not been led here through a narrow hallway by the Facilitators I’d have thought we were looking into a courtyard, for its shape was that of an upturned coffin, the walls of the space were lined with a maroon fabric that scaled into a darkness. A dim light source meant that I could make out, in the glim, bodies naked and convulsing, in the middle of the space, covered in an oily substance. A few cameras stood on tripods, with their red ‘on’ lights blinking. All that separated me was an A4, stuck to the glass partition wall, reading…

CUDDLE

WORKSHOP